See my online slides here:

Introduction

"Third-generation" of Moral Behavior theory

- second-generation: induce social preference, but cannot explain all the thinge.g. people want help others, but dislike helping-too-much behavior

- based on a general model of identity management and self-inference mechanism

- model of motivated belief

Model

- let moral identity and similar concepts as beliefs about one's deep "values"

- emphasizes the self-inference process through which they operate

- the needs served by particular beliefs are linked to more basic aspects of preferences

- demand side: affective benefits (hedonic value of self-esteem, or anticipatory utility from one's economicand social assets), functional ones (a strong moral sense of self that helps resist temptations), or both

- "supply side": use imperfect memory or awareness, which emphasizes identity investments as self-signals = judge oneself by own behavior or decisions

Motivating Facts And Puzzles

Unstable Altruism

individual-level

- fairness, cooperation, and honesty in anonymous, one-shot interactions

- excuse seeking, moral wiggle room,

- history dependence:

- foot-in the door effect : an initial request for a small favor (which most people accept) raises the probability of accepting costlier ones later on; similarly, a large initial request (which most people reject) reduces later willingness togrant a smaller one (see DeJong 1979).

- moral credentialing: acting as if an initial good behavior (again, exogenously induced) provided a license to misbehave later on

- nonmonotonicity

Coexistence Of Social And Antisocial Punishments

group-level

free-riders in public-good games, and violators of social norms more generally, get punished by others (e.g., Fehr and G ̈ achter 2000)

who behave too well—exhibiting stronger moral principles or resilience than their peers (objectors to injustice, vegetarians, and whistle-blowers) or contributing "excessively" to public goods—also elicit resentment, derogation, and punishment from their peers

Taboo Tradeoffs

- not make utility tradepoffs; but considered immoral to place a monetary value on marriage, friendship, or loyalty to a cause;

- no consideration for markets for organs, genes, sex, surrogate pregnancy andadoption

- "mere contemplation" effect: when prompted to simply envision or speculate about tradeoffs between sacred and secular values, subjects respond with noncompliance, outrage, and later symbolic acts of moral cleansing. people seek to enforce such taboos not only on others' behavior (which could be accounted for by standard externalities) or even on their own(precommitment), but even on their own thoughts and cognitions.

THE MODEL

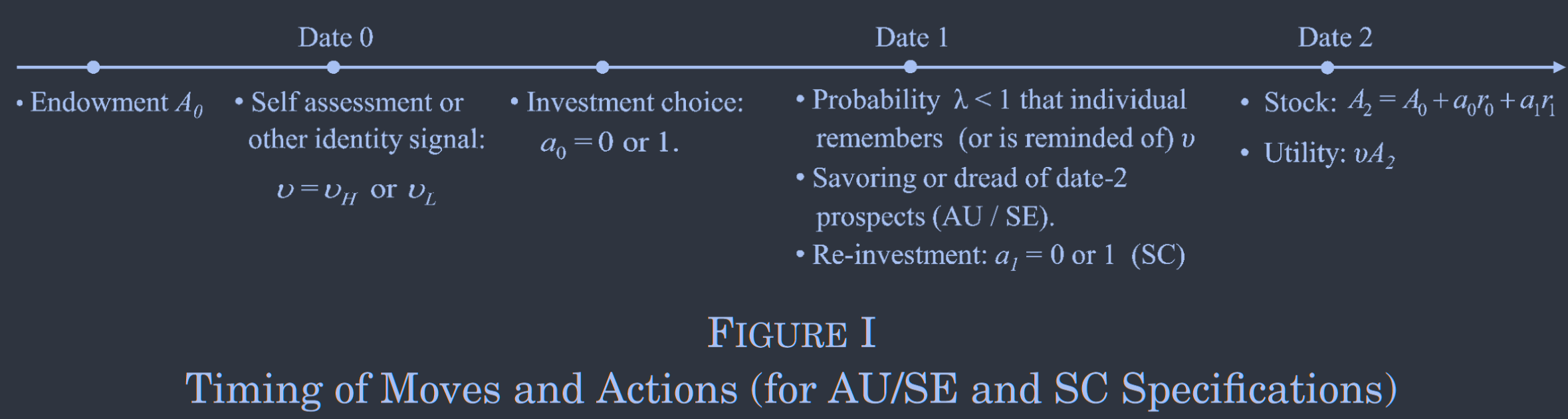

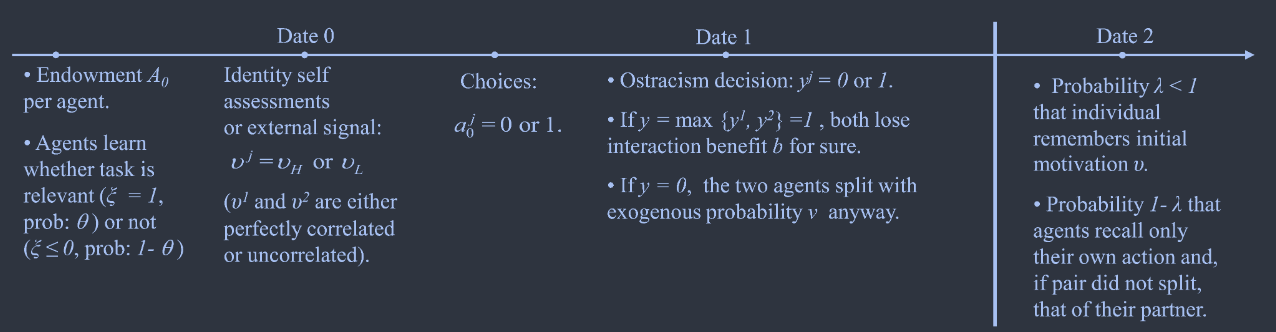

Timing of Moves and Actions

Preferences and Beliefs

one-shot interaction(no use to build social network):

but the behavior still release a signal of what he is (for self-inference)

Date 0. self-assessment

the agent has access to a signal about his type(good or bad)

prior expectation:

Assumption 1

The net cost of investment at date

Because a more prosocial individual internalizes more of the benefits accruing to other people, even in one-shot interactions, he finds it (weakly) less costly to act morally—help, refrain from opportunism

Date 1. Supply side of Motivated Belief

Assumption 2. (Self-inference)

the individual is aware of his true valuation v only with probability

denote

so with probability

💡

Assumption 3.

The value function

Assumption 4. Exclude the Trivial Case

the investment cost is too low so that both types always invest regardless of identity concerns

we assume:

Date 2. Future, used for following AU case

Benchmark Cases

Demand for beliefs 1: self-esteem / anticipatory utility

self-esteem (SE)

preference given by

anticipatory utility (AU): more consequentialist

what is AU: hopefulness, anxiety, or dread that arise from contemplating future and social prospects

define long-term welfare:

family, friends, colleagues, ethnic group, etc.

Date 1: utility=

Another important determinant of s is salience

Pure Anticipatory Utility (at Data 1)

no further decision to be made at date 1,

the continuation value (evaluated from t = 0) of entering period 1 with

for

for

s/δ reflects also the relative lengths of periods 1 and 2

Assumption 2 is satisfied

self-esteem is a special case of anticipatory utility

SE is AU when

so

welfare analysis: total intertemporal utility

where the expectation is taken with respect to the prior distribution

Demand for beliefs 2: self-control

self-control (SC)

Maintaining a strong, stable sense of identity also has functional value, helping one to make consistent choices and resist harmful temptations

the context of social interactions, which inherently feature a tradeoff between short-term gains from selfishness (or emotional release) and long-run benefits from behaving morally.

long-term welfare

long-term welfare still be

moral decision

moral decision happen in

assumption for simplicity

(smooth over t = 1 decisions, so as to make V differentiable)

- Investment at

involves a stochastic cost - type-independent distribution

on ( can be relax)

Perception of the cost of acting morally

At date 1, weakness of will make the immediate gains from opportunism more salient than its distant consequences, thus perceives the cost of acting morally as

This condition implies that whenever the agent (either H type or both) chooses to behave cooperatively, it is ex-ante efficient for him to do so

moral identity and self-restraint

given a self-view

a threshold cost level that increases with

a stronger moral identity generates valuable self-restraint

continuation value increases in

Assumption 2 are satisfied if

welfare analysis

because the agent will generally have present-biased preferences at date 0, just like at date 1. Thus, if

V is also an ex-ante value function, our welfare criterion will be:

Mixed Case

determine when anticipatory emotions alleviate or worsen the self-discipline problem

will be examined in Section VI

Interpreting the Model

tell us it is more applicable than the text suggest(cry)

Identity as Multidimensional

identity is single dimentional in model

The model can represent a tradeoff between two dimensions A and B, such as morality and wealth, or family and career, linked by uncertainty over their relative value

A second type of identity conflict, arising from rivalry in consumption rather than investment, is analyzed in Section VI.C

Identity as a Social Object

In our main illustration,

Self-Knowledge and Affirmation of Values

The assumption that people have imperfect insights into their own values and motives admits several formally equivalent interpretations:

- A moral sentiments view, in which people experience guilt or pride not only when actually observed by others, but also from the virtual judgements of "imagined spectators" (Smith 1759).

- An ego-superego view, in which v is simultaneously known at the subconscious level and not known at the conscious level (Bodner and Prelec 2003). This corresponds in the model to a limiting case of "instantaneous forgetting."

- Intergenerational transmission. In this polar case "forgetting" takes a generation, so the date-0 agent is a parent and the date-1 agent his child. Parents have experience with the value of certain assets, such as the life satisfaction derived from social bonds versus money and career, or the benefits that religion might yield. Children start less informed and learn (with probability 1 − λ) from the example that their parents set, or from what they force them to do (a0) . Parents strive, altruistically or selfishly, to inculcate in their children "values" (beliefs

) that will enrich their lifetime experience or lead them to take desirable actions.

Equilibrium And Welfare: Solving the model

Behavior

each type chooses his optimal option

denotation of

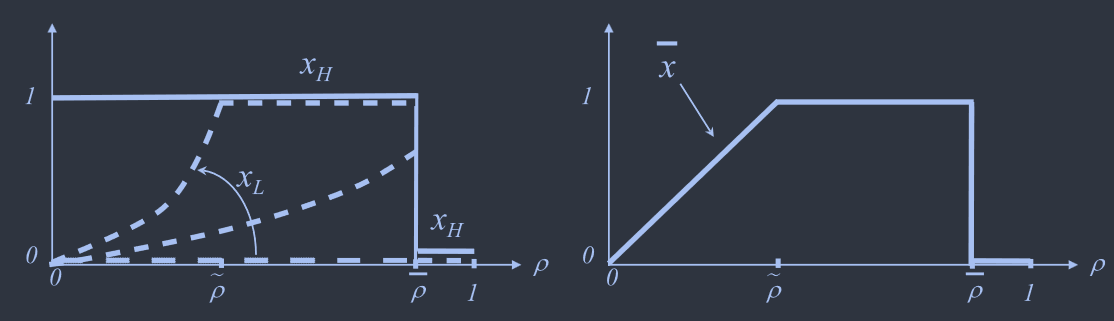

respective probabilities that types

where

expected value function

which brings together the demand (preferences) and supply (cognition) sides

inheriting from V all the properties in Assumption 3

Investment(t = 0) is optimal when:

The Sorting Condition. net return to "good behavior" is greater for the H type than the L one, implying that

Reason:

- H type has a lower effective cost

- when

, the agent attaches greater value to any increment to the capital stock - when

, the agent also cares more about having a "strong" identity at date 1, which investing helps achieve if

monotonic Perfect Bayesian equilibria

- the H type always invests more:

,which given again means that whenever - a (stronger) form of monotonicity is also imposed on off-the-equilibrium-path beliefs if

,then if ,then This refinement is intuitive and does not affect any qualitative results. - over a certain range of parameters there may be multiple (three) monotonic equilibria, among which one is Pareto-dominant and will be selected

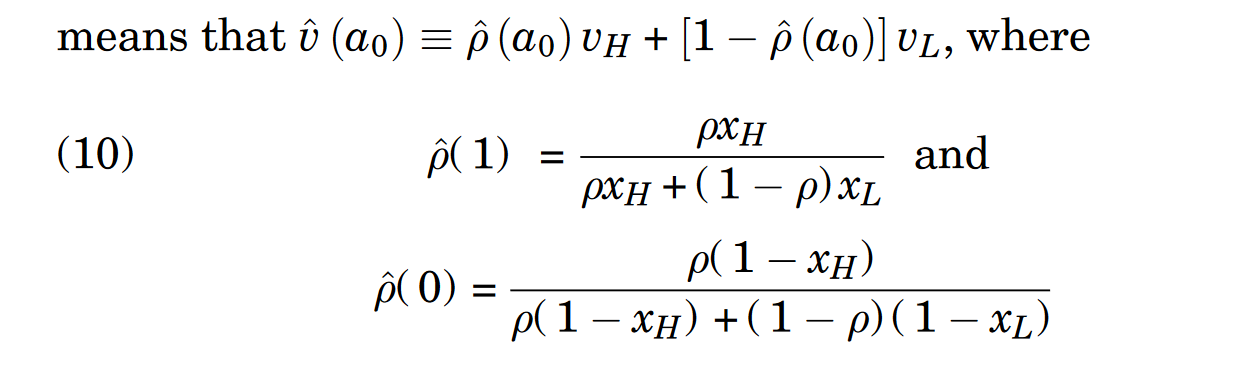

Proposition 1.

There exists a unique (monotonic, undominated) equilibrium, characterized by thresholds

for and for is non-decreasing on ,equal to 1 on when and equal to 0 on .

Left panel: solid line

Right panel: average investment

No Investment.

When initial self-image is good enough, the H type can afford not to invest, since the other one also behaves opportunistically the posterior will equal the prior, which is already close to 1 and thus could not be increased much anyway

Investment Cases.

H invest to "stand for his principles" and separate from the L type

Separation. When

is sufficiently high, the low-valuation type does not find it worthwhile to invest , whereas the high-valuation type does. Randomization.

For lower values of

, L type intend to imitate the H type but ability of imitation is limited by the prior

Universal Investment.

For

still lower, even a small gain in self-image is worth pursuing, so . is above the threshold (which increases with )

Proposition 2. Comparative-Statics Predictions

- An individual invests more in identity if

- the more malleable his beliefs (the lower λ);

- the lower the investment cost (the lower

or ) - the more salient the identity in the SE/AU case (the higher s)

- the higher the capital stock

in the AU case

- Initial beliefs have a non-monotonic, hill-shaped effect on overall investment

increases linearly on , equals 1 on , then falls to 0 beyond.

Implications and Evidence on Moral Identity and Behavior

Malleability of Beliefs

If the individual have better ability to know his true preferences and motives(lower

moral wriggle room / self-concept maintenence theory / Delegation

= presence and power of self-deception

Salience of Identity

Mazar, Amir, and Ariely (2008). honesty promoted after read the Ten Commandments

consumption on "symbolic" goods such as carbon offsets, green products, largely spurred by advertising campaigns that manipulate the salience of people' self (and social) image.

The fact that most of the same households vote against environmental taxes, together with experiments documenting the moral-licensing effects of green purchases (Mazar and Zhong 2010), provides further support for the idea that such expenditures are in large part identity investments.

Uncertain Values

overall (ex-ante) probability of investment

is hill-shaped with respect to ρ investing in self-reputation has a low return when the prior is low, and is not needed when it is already high

- identity-affirming behaviors are characteristic of people with unsettled preferences and values; hence the moral zeal of the newconvert (religious or political), or the exacerbated nationalism of the recent immigrant

- the predicted hill-shape of behavior with respect to ρ can help reconcile two contradictory sets of experimental findings on people's responses to manipulations of their self-image

Threats to a strongly held identity. "transgression-compliance" effct: subjects who are led to believe that they have harmed someone (by administering painful electric shocks, or carelessly ruining some of her work) show an increased willingness to later on accept requests to perform a good action

Manipulating weaker aspects of identity. when ρ changes marginally, starting from below ̃

"foot in the door" effect

Identity and Welfare: Treadmill Effect or Empowerment

Self-esteem/Anticipatory Utility and the Treadmill Effect

based on

we get:

is constant: although agents actively manage their self-views, this is a zero-sum game across types, by the law of iterated expectations and : always (weakly) decrease as identity investments rise in response to a greater malleability of beliefs, 1−λ

an increase in his capital stock can also make the individual worse off.

the condition for a no-investment equilibrium

treadmill effect

higher asset levels do no generate much of an increase in life satisfaction, or may even reduce it—and this precisely due to a self-defeating pursuit of the belief that these assets will ensure happiness, or forestall misery

a moral treadmill is much less likely than a material one

Diminishing marginal utility of consumption thus makes a treadmill effect in material pursuits likely at high wealth levels, but a non-issue for the poor.

Personal relationships and good deeds are arguably less subject to decreasing returns—those may even be increasing, through network effects and the spreading of reputation.

Proposition 3. In the anticipatory utility or self-image case:

- An increase in the malleability of beliefs

always reduces welfare. - An increase in (per se valuable) capital

can make the individual worse off. - An increase in salience

can also lower welfare

Willpower and the Commitment Value of Identity

basic self-control version of the model,

The malleability of beliefs, on the other hand, now affects behavior both at t = 0 and at t = 1

suppose 2 cases:

- λ = 1, neither type behaves prosocially at t = 0:

,so - for some λ < 1, the equilibrium involves mixing: the more altruistic type always cooperates

, while the more selfish one randomizes

difference in intertemporal welfare is:

while

first term: how, when the L type invests at t = 0, this strengthens his moral self-regard and thereby raises his subsequent propensity to behave well

such pooling at t = 0 dilutes the identity of the H type, self-doubt increases the likelihood that he will be succumb to opportunism

Since prosocial investment at t = 1, when it occurs, is always ex-ante optimal (by Equation (6)), the first effect leads to a welfare gain, the second to a loss

Turning now to the direct contribution of date-0 behavior to intertemporal welfare, if β is low enough that (say) the first two terms in Equation (15) are positive, ex-ante efficient investments fail to occur in period 0 if λ = 1: from the very start, the agent behaves too opportunistically for his own good. The ability to affect his self-image ( λ < 1) provides additional motivation for acting prosocially at t = 0, which then directly raises ΔW. When the first two terms in Equation (15) are positive, conversely, such good behavior entails a net cost, which only pays off in terms of improved self-restraint at t = 1 if E[ΔV] sufficiently positive.

Proposition 4. In the self-control case, more malleable beliefs (lower

Taboos and Transgressions

distinguish two complementary ways in which they operate—ex ante and ex post

- self enforced, aims to avoid dangerous (self-) knowledge that might surface from "cold" analytical contemplation of what short-run tradeoffs might be available or expedient

- socially enforced, is a form of information destruction aimed at repairing the damage to beliefs caused when someone, through his actions or speech, has violated a norm or taboo.

Self-enforced taboos: Information Avoidance

"To compare is to destroy." (Fiske andTetlock 1997)

Setting

type

Let

Selling decision of Assets

Suppose

price distribution is:

Selling decision depends on price found

let

when

when

Choice

contemplation is done once check: he will recall that he contemplated the possibility of a transaction and evaluated whether maintaining his identity or dignity was "worth it"

assumption: transaction must with price checking

transacting without first finding out the price is either infeasible, or else unprofitable.

Taboo holding Condition

Positive Side of Conclusions

How taboos arise and are sustained

special case of former model: where

full-investment equilibrium or predominantly by the more committed (mixing or separating equilibrium), depends on the initial strength of beliefs

Taboo's Reaffirmation or Collapse

according to which side of the "hill" (Figure II, right panel) the induced erosion of ρ occurs on

on the right side: ρ decrease → reaffirmation

on the left side: ρ decrease → collapse

Normative side

Propositions 3 and 4 show how the welfare effect of taboos depends on whether they reflect anticipatory or self-control motives. In the first case, upholding taboos generally lowers an individual's ex-ante welfare. In the latter it can be beneficial, but only under specific conditions involving the severity of the selfcontrol problem.

Proposition 3. In the anticipatory utility or self-image case:

- An increase in the malleability of beliefs

always reduces welfare. - An increase in (per se valuable) capital

can make the individual worse off. - An increase in salience

can also lower welfare

Dealing with Sinners and Saints: Information Destruction

socially enforced taboos: understand the coexistence of both social and antisocial punishments

benchmarking idea

people compare themselves to others who they feel are akin to them or face a similar environment while asseing a person's type

- Deviant behavior

: sends a negative signal about the value of the existing capital stock (anticipatory utility version) or that of motivation-sensitive future investments (imperfect willpower version) - Good behavior: lapsed individual is oneself, and by peers that is threatening to the self-concept, as it takes away potential excuses involving situational factors or moral ambiguity

In either case, the exclusion of mavericks from the group suppresses the undesirable reminders created by their presence: "out of sight, out of mind." That is, exclusion lowers λ

The Person and the Situation

New elements:

- Action of benefit society or not

. - with ex-ante probability θ, agent have an "excuse" for deviate from the groupin former case = choosing

is useless—maybe harmful—to the rest of society, or where the private cost is so high that even the most moral types (H) would choose - With ex-ante probability 1−θ, the action

is socially beneficial, the return of relational capital is ξ = 1 when the action benefit others and ξ ≤ 0 when not , different from before, reflecting the fact that a more prosocial agent is less inclined to engage in a socially harmful action.

- with ex-ante probability θ, agent have an "excuse" for deviate from the groupin former case = choosing

- Action of exclusion from group or not

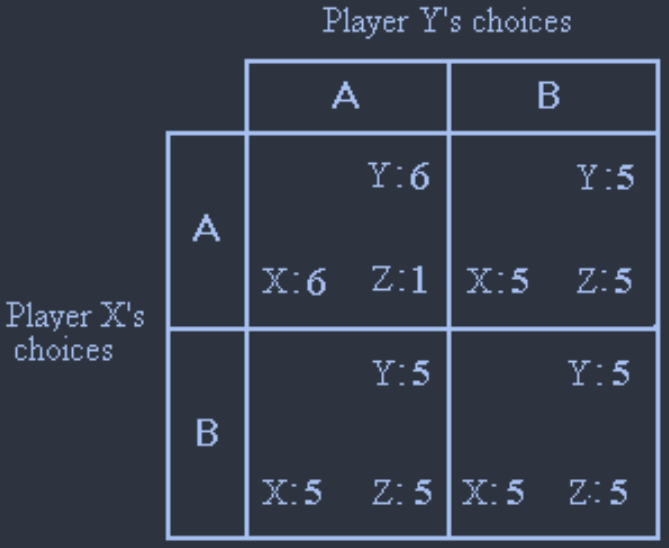

two agents after observing each other's action, decide whether to continue in the relationship or to break it if someone exit, both lose b as future interactions benefit - Agent i's utility function

date 1: (no-recall assumptions) each agent always remains aware of his own behavior

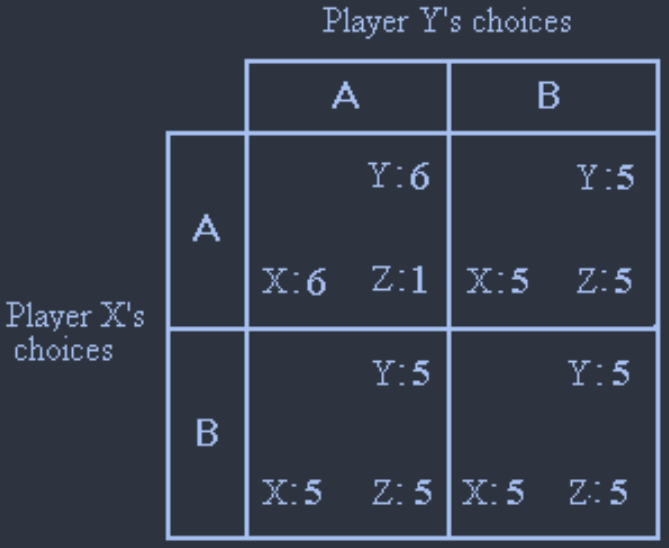

Benchmarking on the Person

two individuals' values are perfectly correlated

date-0 contribution is always socially useful

two individuals' values are perfectly correlated:

Benchmarking on the Situation

the two types are independent

social usefulness (ξ = 1, with probability θ) or absence(ξ ≤ 0, with probability 1 − θ) of the date-0 contribution is situation-specific, and the same for both agents

When faced with a given situation agents are able to assess ξ, but later on it, too, is subject to imperfect recall (or self-serving memory distortion) with probability 1 − λ.

focus on symmetric equilibria (in undominated strategies) in which the more altruistic type always invests when ξ = 1 and no one invests when ξ ≤ 0 (either ξ is sufficiently negative, or ξ = 0 and the value of self-image is low enough).

Proposition 5. In an equilibrium such that the H type invests when it is socially useful (ξ = 1), let x ∈ [0, 1] denote the probability of investment by the L type.

- Ostracism (y = 1) occurs only when actions differ, i.e. one agent invests and the other not.shows how a value of social conformity (strategic complementarity) arises endogenously from individual concerns over self -image because each agent has an incentive to exclude those who act differently from him

- Social punishment and Anti-social punishmentostracism comes from the virtuous agent

when benchmarking is on the personostracism comes from the unvirtuous one when benchmarking is on the situation.correspond to experimental eveidence: free-riders in public-good games get punished, but also who exhibit stronger moral principles or contribute "too much" to public goods are get punished - With both the AU/SE and SC specifications and under either type of benchmarking, there exists a (positive -measure) range of parameters such that both

and are equilibria:shows cross-society-differences in civic norms and how they are enforced - When benchmarking is on the person, x = 1 is sustained by the ostracism of "sinners" (a prosocial norm), while

involves no ostracism - When benchmarking is on the situation, x = 0 is sustained by the ostracism of "do-gooders" (an antisocial norm), while x = 1 involves no ostracism

- When benchmarking is on the person, x = 1 is sustained by the ostracism of "sinners" (a prosocial norm), while

shows cross-society-differences in civic norms and how they are enforced

Questions

why not use a general price distribution?

there may be two signals of an agent's type: whether check the price and, if so, whether he transacted or not, given the price.

to isolate the effects("priceless" effect and "mere-contemplation" effect)